Brex Sale to Capital One: A Letdown for Late-Stage Investors But a Big Win for Founders

Plus, secondary markets are humming as investors scrap for a piece of top private companies

The Week in Short

Brex deal is a Rorschach test on exit expectations. Secondary volumes soar as investors chase big names. The AI boom is no dot-com bubble, says a16z, which also promoted two investors to GP. Humans& and Inferact score nine-figure “seed” rounds. Zipline and OpenEvidence also raise big bucks. OpenAI preps ads, seeks new Middle East funding, and sees device launch this year. Anthropic’s new funding round will value the company at $350 billion, or more. Greenoaks and Altimeter sue the South Korean government, which they say has it in for Coupang. Oracle and Silver Lake win big in long-delayed TikTok deal.

The Main Item

Brex’s $5.15 Billion Exit is a Healthy Reality Check for Non-AI Startups

Depending on how you look at it, Brex’s sale to Capital One for $5.15 billion is a humbling escape hatch or a huge victory.

The glass half empty view is that this exit is a far cry from Brex’s $12 billion valuation in 2022. That round, led by TCV and Greenoaks, was in hindsight a tad optimistic. (Greenoaks also led an earlier round into Brex at a $1 billion valuation.) For an investor like Kleiner Perkins, which spearheaded a $100 million round in June 2019 at $2.5 billion, this will amount to roughly a 1.2x to 1.3x return after dilution — not the type of multiple you want to see after six-and-a-half years. Besides Ribbit Capital and Y Combinator, many investors seem to have overpaid for Brex.

The glass half full view is that $5.15 billion is a lot of money! And this isn’t play money. Brex is getting paid half in cash and half in Capital One’s liquid public stock — not some startup’s questionably inflated equity. The company took in around $1.5 billion in total funding since its founding nine years ago.

“Some of your readership might say why is that only $5.15 billion,” Brex’s Chief Business Officer Art Levy said to me. “Those people haven’t spent enough time in the public markets.” The deal represents “a very strong gross profit multiple for us — a number and transaction value that we’re very proud of,” Levy said.

For Brex founder Pedro Franceschi — the company’s CEO who went the distance after co-CEO Henrique Dubugras took his eye off the ball — this is a safe landing for a vessel that had been in choppy waters.

Of course, half the reason we care about Brex is because it was a protagonist in one of the great startup rivalries: Brex vs. Ramp. Ramp raised at a $32 billion valuation in November. Founders Funds’ resident troll Delian Asparouhov tweeted “GG WP EZ NO RE” — gamer speak for good game, well-played, easy, no rematch. In other words: total Ramp victory. Ramp CEO Eric Glyman (a friend) posted congratulations on X that referenced his stint at Capital One after his first startup, Paribus, sold to the credit card company.

For the broader startup ecosystem, the Brex deal is a reality check. If you’re not an AI company, we’ve actually been in a pretty brutal post-pandemic downturn. On the public markets, that’s evident. Figma, for one, is down 76% from its post-IPO peak. Public market investors don’t seem to hold Silicon Valley’s high-flyers in quite the same esteem as their private-market counterparts.

In terms of great rivalries, there are plenty to watch for. We’ve got Rippling and Ramp on a collision course. And if Capital One can make the most of its acquisition, it could soon have Ramp directly in its crosshairs. Brex had tried to duck too much direct competition with Ramp, exiting the small-and-medium-size business market where Ramp and Capital One compete directly. This showdown may not be done quite yet.

Private Markets

Secondary Sales Ride High, Powered by a Handful of Hot Startups

The jury is still out on whether 2026 will bring a major rebound in tech IPOs, but in the meantime secondary share sales are going strong, with global volume growing 46% to $226 billion in 2025, according to a new report from Evercore.

Institutional traders continue to buy their way into the market. The Swedish firm EQT this week announced the acquisition of secondaries specialist Coller Capital for $3.7 billion. That deal comes on the heels of a flurry late last year that included Goldman Sachs’ purchase of Hans Swildens’s secondaries-heavy Industry Ventures, Charles Schwab’s acquisition of Forge Global, and Morgan Stanley’s buyout of EquityZen.

Secondary deal volume is still dominated by a handful of startups, says Dan Gray, the venture capital thought leader and Odin research lead. Secondary marketplace Hiive’s Hiive 50 Index, which shows which companies’ shares are traded most often, ranks Kraken, SpaceX, Perplexity, and Cerebras as the most active.

Demand for shares in the hottest growth-stage startups is supercharged by investors who are happy to pay a premium via special purpose vehicles so they can boast of having a stake. “A big part of this is logo-hunting firms — they’ll go into a three-layered SPV just so they can add a SpaceX logo to their next fundraising deck,” said Gray.

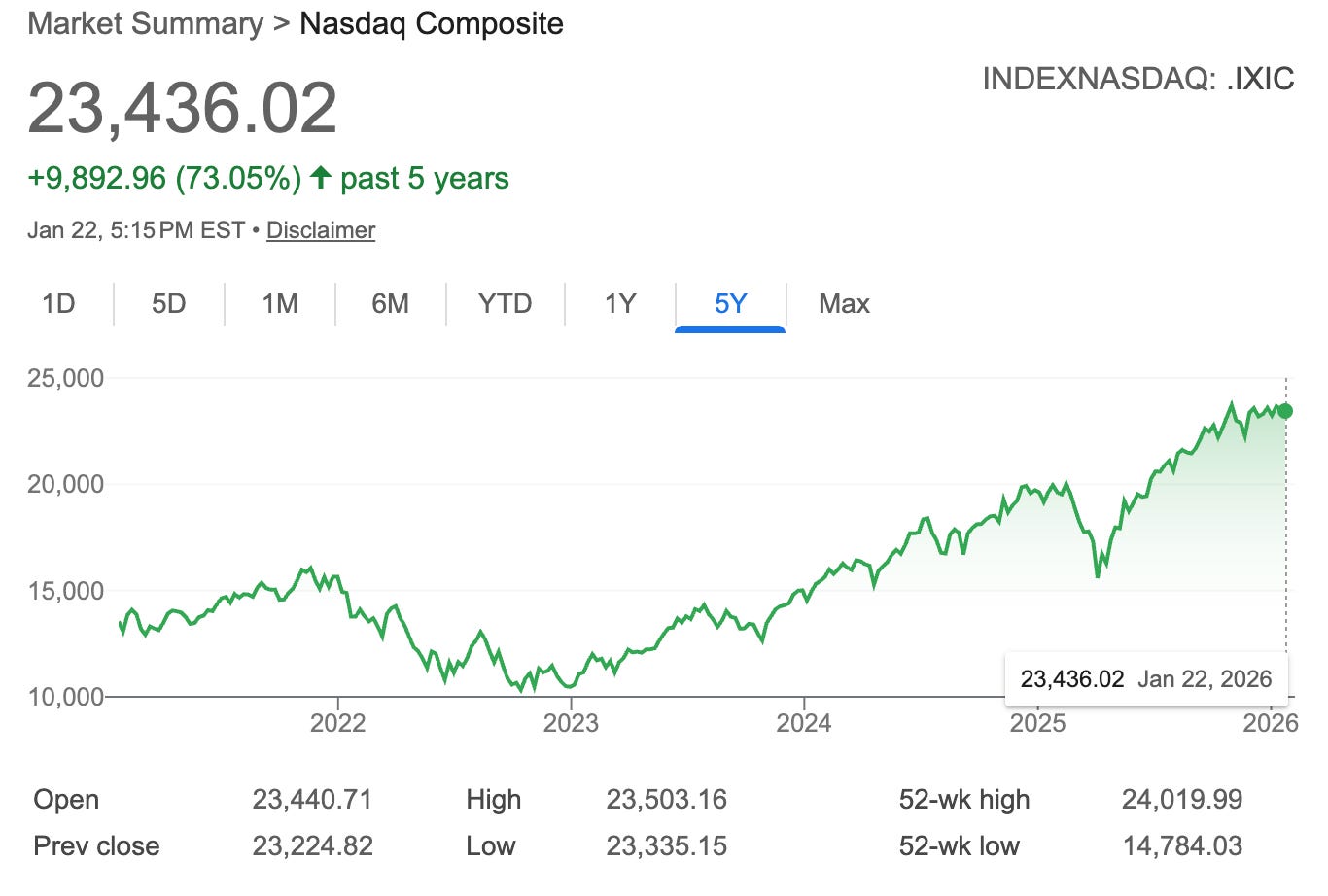

Secondary indexes can also show on the aggregate if startup valuations are remaining overinflated or if buyers are gearing up for a market correction. The Notice50 Index of secondary share values, shown below, saw a steady increase all through 2025, but it peaked on January 9 and has since dropped off slightly. It shows a five-year gain in value of 214.74%. The NASDAQ index, by comparison, rose 73% over the same period.

Notice also shares a list of which shares saw the biggest gain in value over the last 30 days. Their top three as of yesterday were Cerebras, Anthropic, and Cursor.

Two Big Charts

AI Mania Hasn’t Reached Dot-Com Levels of Precarity, Says a16z

The debate over whether the AI boom is a dangerous bubble continues to rage, but a16z says there’s no reason to fear. Earnings multiples of AI companies are much more balanced compared with the peak of the dot-com bubble, data from the firm’s latest State of Markets report shows.

Similarly, the ratio of CapEx to company sales, while increasing, is still well below the previous peak. The share of CapEx that is coming from outside debt, rather than from internally generated cash flow, is also significantly lower than it was in the dot-com era.